Tuesday, December 31, 2013

Monday, December 30, 2013

Sunday, December 29, 2013

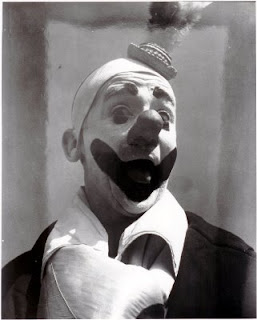

AL MIACO: "The Greatest Living Clown (1880s)

|

| Al Miaco on Ringling in 1915 |

Saturday, December 28, 2013

Friday, December 27, 2013

Thursday, December 26, 2013

Tuesday, December 24, 2013

Monday, December 23, 2013

Sunday, December 22, 2013

Saturday, December 21, 2013

Friday, December 20, 2013

Wednesday, December 18, 2013

Saturday, December 14, 2013

Tuesday, December 10, 2013

Friday, December 06, 2013

Thursday, December 05, 2013

Monday, December 02, 2013

Sunday, December 01, 2013

Thursday, November 28, 2013

Thursday, November 21, 2013

Wednesday, November 20, 2013

IN MEMORIAM: Charles "Spuggy" Wardell (April 10 1931, died May 13 2013)

From The Telegraph...

His real name was Charles Wardell. Born in Leeds on April 10 1931, he was adopted as a baby by a travelling showman known as Newcastle Jack Taylor, a prize fighter who lugged his own boxing booth round traditional fairs in the north of England.

Young Charles left school as soon as he could to enlist in the Army and, from 1948 to 1953, served as a sergeant in the Green Howards in Suez, Malaya and Austria.

Returning to Britain, he began his career as a comedy act at working men’s clubs and as a children’s entertainer at Warner’s holiday camps, before a chance meeting with Ronnie Smart, son of the circus tycoon, led to his joining Billy Smart’s New World Circus as a clown in 1962. He took his circus name Spuggy from the nickname — “Spuggy-legs” (“spuggy” is Yorkshire slang for “sparrow”) — that had been bestowed on him by his mates in the Army.

He quickly became one of the circus’ most popular attractions, doubling as a hard-riding scout in Smart’s Wild West Spectacular, which closed every show.

After five years he left Smart’s and travelled to South Africa, where he joined the Doyle Brothers’ Olympic Circus. His departure from Britain took place amid some acrimony when, at the dockside, he was accosted by members of Billy Smart’s Circus management who prevented him from leaving with a valuable circus chimp he had adopted and nursed back to good health. Spuggy claimed that Billy Smart himself had given him the animal, and newspapers reported the “Tears of a Clown” as the police intervened to take the chimp off his hands.

In South Africa, Spuggy appeared in partnership with a dwarf clown called Tickey, but his success there was short lived: when one of the Doyle brothers died, the season was aborted after four months. He went on to tour the continent with a travelling exhibition featuring a huge 79ft preserved whale, and later with a performing dolphin show, before finding more sedentary employment as a hotel manager.

He eventually returned to England, and to Smart’s, where the chimp incident had been forgiven and forgotten, continuing to perform with the circus until 1971.

He then took himself off to Germany where, over the next 10 years, he appeared with some of the country’s best-known circuses, including the Althoff family circus. In 1978 he was chosen by the American Circus Ringling Brothers to appear at the International Circus Festival of Monaco, where he was presented with a gold medal by Prince Rainier.

Though he made his home in Germany, when his health declined Spuggy returned to England, finally retiring to Leeds, where he gave occasional performances in aid of children’s charities. Spuggy the Clown’s first marriage was dissolved. He is survived by his second wife, Deborah, and by Gillian, the daughter of his first marriage who married one of Germany’s leading animal trainers.

|

12th December 1964 Spuggy, the clown at Billy Smarts Christmas Circus, being treated by Knoble the chimp, assisted by Daphne Murgatroyd,an assistant at Leeds General Infirmary.

Thursday, November 07, 2013

EVERYTHING OLD IS NEW AGAIN: Abbott & Costello Meet Key & Peele

Begin with the diner scene at the 9:00 mark.

Now take this routine that Abbott & Costello did on the Colgate Comedy Hour in 1952...

And compare it with this Key & Peele sketch from 2013...

Now take this routine that Abbott & Costello did on the Colgate Comedy Hour in 1952...

And compare it with this Key & Peele sketch from 2013...

Friday, November 01, 2013

Thursday, October 31, 2013

Saturday, September 07, 2013

Thursday, September 05, 2013

Wednesday, September 04, 2013

Tuesday, September 03, 2013

Monday, September 02, 2013

Sunday, September 01, 2013

Saturday, August 31, 2013

Friday, August 30, 2013

Thursday, August 29, 2013

Thursday, August 15, 2013

Wednesday, August 14, 2013

Monday, August 12, 2013

RBB&B CLOWN ALLEY: Volkswagen Commercial (1970)

The OP states that this Volkswagen commercial was released in 1970. I would seriously doubt that as most of these performers were no longer with the Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey Circus in 1970.

I would suppose that it is from no later than 1966 since Dennis Stevens and Albert White left for the Beatty-Cole show at the end of that season.

Lou Jacobs and Prince Paul Alpert guide the car into the ring.

Michael "Coco" Polakovs is the first one out followed by Freddie Freeman, Albert "Flo" White, Johnny Day, Owen "Duffy McQuade, Marcus Drougett, Walter Guice, Kinko Sunberry, Gene Lewis, Bobby Johnsen, Dennis Stevens, Duane "Uncle Soapy" Thorpe, Mark Anthony, Lou Jacobs, Barry Sloane on stilts and Frankie Saluto from underneath the fat lady, which would have been funnier if it was Flo White in drag.

Notably absent from that Alley would be Billy Ward and Otto Griebling.

Sunday, August 11, 2013

Saturday, August 10, 2013

Thursday, August 08, 2013

BILLY WILDER: 10 Rules of Good Filmmaking (Most of Which Apply to Clown Gags As Well)

|

| ICHoF inductee Billy Vaughn and partner in performance at Ringling Bros. and Barnum and Bailey Circus World in Haines City, Florida, June 1977. |

Billy Wilder’s Ten Rules of Good Filmmaking:

1: The audience is fickle.

2: Grab ‘em by the throat and never let ‘em go.

3: Develop a clean line of action for your leading character.

4: Know where you’re going.

5: The more subtle and elegant you are in hiding your plot points, the better you are as a writer.

6: If you have a problem with the third act, the real problem is in the first act.

7: A tip from Lubitsch: Let the audience add up two plus two. They’ll love you forever.

8: In doing voice-overs, be careful not to describe what the audience already sees. Add to what they’re seeing.

9: The event that occurs at the second act curtain triggers the end of the movie.

10: The third act must build, build, build in tempo and action until the last event, and then—that’s it. Don’t hang around.

Saturday, August 03, 2013

The History and Psychology of Clowns Being Scary by Linda Rodriguez McRobbie (Smithsonian.com)

|

| Bernie Kallman |

There’s a word— albeit one not recognized by the Oxford English Dictionary or any psychology manual— for the excessive fear of clowns: Coulrophobia.

Not a lot of people actually suffer from a debilitating phobia of clowns; a lot more people, however, just don’t like them. Do a Google search for “I hate clowns” and the first hit is ihateclowns.com, a forum for clown-haters that also offers vanity @ihateclowns.com emails. One “I Hate Clowns” Facebook page has just under 480,000 likes. Some circuses have held workshops to help visitors get over their fear of clowns by letting them watch performers transform into their clown persona. In Sarasota, Florida, in 2006, communal loathing for clowns took a criminal turn when dozens of fiberglass clown statues—part of a public art exhibition called "Clowning Around Town" and a nod to the city’s history as a winter haven for traveling circuses—were defaced, their limbs broken, heads lopped off, spray-painted; two were abducted and we can only guess at their sad fates.

Even the people who are supposed to like clowns—children—supposedly don’t. In 2008, a widely reported University of Sheffield, England, survey of 250 children between the ages of four and 16 found that most of the children disliked and even feared images of clowns. The BBC’s report on the study featured a child psychologist who broadly declared, “Very few children like clowns. They are unfamiliar and come from a different era. They don't look funny, they just look odd.”

But most clowns aren’t trying to be odd. They’re trying to be silly and sweet, fun personified. So the question is, when did the clown, supposedly a jolly figure of innocuous, kid-friendly entertainment, become so weighed down by fear and sadness? When did clowns become so dark?

Maybe they always have been.

Clowns, as pranksters, jesters, jokers, harlequins, and mythologized tricksters have been around for ages. They appear in most cultures—Pygmy clowns made Egyptian pharaohs laugh in 2500 BCE; in ancient imperial China, a court clown called YuSze was, according to the lore, the only guy who could poke holes in Emperor Qin Shih Huang’s plan to paint the Great Wall of China; Hopi Native Americans had a tradition of clown-like characters who interrupted serious dance rituals with ludicrous antics. Ancient Rome’s clown was a stock fool called the stupidus; the court jesters of medieval Europe were a sanctioned way for people under the feudal thumb to laugh at the guys in charge; and well into the 18th and 19th century, the prevailing clown figure of Western Europe and Britain was the pantomime clown, who was a sort of bumbling buffoon.

But clowns have always had a dark side, says David Kiser, director of talent for Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey Circus. After all, these were characters who reflected a funhouse mirror back on society; academics note that their comedy was often derived from their voracious appetites for food, sex, and drink, and their manic behavior. “So in one way, the clown has always been an impish spirit… as he’s kind of grown up, he’s always been about fun, but part of that fun has been a bit of mischief,” says Kiser.

“Mischief” is one thing; homicidal urges is certainly another. What’s changed about clowns is how that darkness is manifest, argued Andrew McConnell Stott, Dean of Undergraduate Education and an English professor at the University of Buffalo, SUNY.

|

| Harry Dann |

Stott is the author of several articles on scary clowns and comedy, as well as The Pantomime Life of Joseph Grimaldi, a much-lauded 2009 biography of the famous comic pantomime player on the Regency London stage. Grimaldi was the first recognizable ancestor of the modern clown, sort of the Homo erectus of clown evolution. He’s the reason why clowns are still sometimes called “Joeys”; though his clowning was of a theatrical and not circus tradition, Grimaldi is so identified with modern clowns that a church in east London has conducted a Sunday service in his honor every year since 1959, with congregants all dressed in full clown regalia.

In his day, he was hugely visible: It was claimed that a full eighth of London’s population had seen Grimaldi on stage. Grimaldi made the clown the leading character of the pantomime, changing the way he looked and acted. Before him, a clown may have worn make-up, but it was usually just a bit of rouge on the cheeks to heighten the sense of them being florid, funny drunks or rustic yokels. Grimaldi, however, suited up in bizarre, colorful costumes, stark white face paint punctuated by spots of bright red on his cheeks and topped with a blue mohawk. He was a master of physical comedy—he leapt in the air, stood on his head, fought himself in hilarious fisticuffs that had audiences rolling in the aisles—as well as of satire lampooning the absurd fashions of the day, comic impressions, and ribald songs.

But because Grimaldi was such a star, the character he’d invented became closely associated with him. And Grimaldi’s real life was anything but comedy—he’d grown up with a tyrant of a stage father; he was prone to bouts of depression; his first wife died during childbirth; his son was an alcoholic clown who’d drank himself to death by age 31; and Grimaldi’s physical gyrations, the leaps and tumbles and violent slapstick that had made him famous, left him in constant pain and prematurely disabled. As Grimaldi himself joked, “I am GRIM ALL DAY, but I make you laugh at night.” That Grimaldi could make a joke about it highlights how well known his tragic real life was to his audiences.

Enter the young Charles Dickens. After Grimaldi died penniless and an alcoholic in 1837 (the coroner’s verdict: “Died by the visitation of God”), Dickens was charged with editing Grimaldi’s memoirs. Dickens had already hit upon the dissipated, drunken clown theme in his 1836 The Pickwick Papers. In the serialized novel, he describes an off-duty clown—reportedly inspired by Grimaldi’s son—whose inebriation and ghastly, wasted body contrasted with his white face paint and clown costume. Unsurprisingly, Dickens’ version of Grimadli’s life was, well, Dickensian, and, Stott says, imposed a “strict economy”: For every laugh he wrought from his audiences, Grimaldi suffered commensurate pain.

Stott credits Dickens with watering the seeds in popular imagination of the scary clown—he’d even go so far as to say Dickens invented the scary clown—by creating a figure who is literally destroying himself to make his audiences laugh. What Dickens did was to make it difficult to look at a clown without wondering what was going on underneath the make-up: Says Stott, “It becomes impossible to disassociate the character from the actor.” That Dickens’s version of Grimaldi’s memoirs was massively popular meant that this perception, of something dark and troubled masked by humor, would stick.

Meanwhile, on the heels of Grimaldi’s fame in Britain, the major clown figure on the Continent was Jean-Gaspard Deburau’s Pierrot, a clown with white face paint punctuated by red lips and black eyebrows whose silent gesticulations delighted French audiences. Deburau was as well known on the streets of Paris as Grimaldi was in London, recognized even without his make-up. But where Grimaldi was tragic, Deburau was sinister: In 1836, Deburau killed a boy with a blow from his walking stick after the youth shouted insults at him on the street (he was ultimately acquitted of the murder). So the two biggest clowns of the early modern clowning era were troubled men underneath that face-paint.

After Grimaldi and Deburau’s heyday, pantomime and theatrical traditions changed; clowning largely left the theater for the relatively new arena of the circus. The circus got its start in the mid-1760s with British entrepreneur Philip Astley’s equestrian shows, exhibitions of “feats of horsemanship” in a circular arena. These trick riding shows soon began attracting other performers; along with the jugglers, trapeze artists, and acrobats, came clowns. By the mid-19th century, clowns had become a sort of “hybrid Grimaldian personality [that] fit in much more with the sort of general, overall less-nuanced style of clowning in the big top,” explains Stott.

Clowns were comic relief from the thrills and chills of the daring circus acts, an anarchic presence that complimented the precision of the acrobats or horse riders. At the same time, their humor necessarily became broader—the clowns had more space to fill, so their movements and actions needed to be more obvious. But clowning was still very much tinged with dark hilarity: French literary critic Edmond de Goncourt, writing in 1876, says, “[T]he clown’s art is now rather terrifying and full of anxiety and apprehension, their suicidal feats, their monstrous gesticulations and frenzied mimicry reminding one of the courtyard of a lunatic asylum.” Then there’s the 1892 Italian opera, Pagliacci (Clowns), in which the cuckolded main character, an actor of the Grimaldian clown mold, murders his cheating wife on stage during a performance. Clowns were unsettling—and a great source for drama.

|

| Bobby Kay |

England exported the circus and its clowns to America, where the genre blossomed; in late 19th century America, the circus went from a one-ring horse act to a three-ring extravaganza that travelled the country on the railways. Venues and humor changed, but images of troubled, sad, tragic clowns remained—Emmett Kelly, for example, was the most famous of the American “hobo” clowns, the sad-faced men with five o’clock shadows and tattered clothes who never smiled, but who were nonetheless hilarious. Kelly’s “Weary Willie” was born of actual tragedy: The break-up of his marriage and America’s sinking financial situation in the 1930s.

Clowns had a sort of heyday in America with the television age and children’s entertainers like Clarabell the Clown, Howdy Doody’s silent partner, and Bozo the Clown. Bozo, by the mid-1960s, was the beloved host of a hugely popular, internationally syndicated children’s show – there was a 10-year wait for tickets to his show. In 1963, McDonald’s brought out Ronald McDonald, the Hamburger-Happy Clown, who’s been a brand ambassador ever since (although heavy is the head that wears the red wig – in 2011, health activists claimed that he, like Joe Camel did for smoking, was promoting an unhealthy lifestyle for children; McDonald’s didn’t ditch Ronald, but he has been seen playing a lot more soccer).

But this heyday also heralded a real change in what a clown was. Before the early 20th century, there was little expectation that clowns had to be an entirely unadulterated symbol of fun, frivolity, and happiness; pantomime clowns, for example, were characters who had more adult-oriented story lines. But clowns were now almost solely children’s entertainment. Once their made-up persona became more associated with children, and therefore an expectation of innocence, it made whatever the make-up might conceal all the more frightening—creating a tremendous mine for artists, filmmakers, writers and creators of popular culture to gleefully exploit to terrifying effect. Says Stott, “Where there is mystery, it’s supposed there must be evil, so we think, ‘What are you hiding?’”

Most clowns aren’t hiding anything, except maybe a bunch of fake flowers or a balloon animal. But again, just as in Grimaldi and Deburau’s day, it was what a real-life clown was concealing that tipped the public perception of clowns. Because this time, rather than a tragic or even troubled figure under the slap and motley, there was something much darker lurking.

Even as Bozo was cavorting on sets across America, a more sinister clown was plying his craft across the Midwest. John Wayne Gacy’s public face was a friendly, hard-working guy; he was also a registered clown who entertained at community events under the name Pogo. But between 1972 and 1978, he sexually assaulted and killed more than 35 young men in the Chicago area. “You know… clowns can get away with murder,” he told investigating officers, before his arrest.

Gacy didn’t get away with it—he was found guilty of 33 counts of murder and was executed in 1994. But he’d become identified as the “Killer Clown,” a handy sobriquet for newspaper reports that hinged on the unexpectedness of his killing. And bizarrely, Gacy seemed to revel in his clown persona: While in prison, he began painting; many of his paintings were of clowns, some self-portraits of him as Pogo. What was particularly terrifying was that Gacy, a man who’d already been convicted of a sexual assault on a teenage boy in 1968, was given access to children in his guise as an innocuous clown. This fueled America’s already growing fears of “stranger danger” and sexual predation on children, and made clowns a real object of suspicion.

After a real life killer clown shocked America, representations of clowns took a decidedly terrifying turn. Before, films like Cecil B. DeMille’s 1952 Oscar-winning The Greatest Show on Earth could toy with the notion of the clown with a tragic past—Jimmy Stewart played Buttons, a circus clown who never removed his make-up and who is later revealed to be a doctor on the lam after “mercy killing” his wife—but now, clowns were really scary.

In 1982, Poltergeist relied on transforming familiar banality—the Californian suburb, a piece of fried chicken, the television—into real terror; but the big moment was when the little boy’s clown doll comes to life and tries to drag him under the bed. In 1986, Stephen King wrote It, in which a terrifying demon attacks children in the guise of Pennywise the Clown; in 1990, the book was made into a TV mini-series. In 1988, B-movie hit Killer Klowns from Outer Space featured alien clowns harboring sharp-toothed grins and murderous intentions. The next year saw Clownhouse, a cult horror film about escaped mental patients masquerading as circus clowns who terrorize a rural town. Between the late 1980s and now – when the Saw franchise’s mascot is a creepy clown-faced puppet -- dozens of films featuring vicious clowns appeared in movie theatres (or, more often, went straight to video), making the clown as reliable a boogeyman as Freddy Kreuger.

|

| Chuck Burnes |

But anecdotally at least, negative images of clowns are harming clowning as a profession. Though the Bureau of Labor Statistics doesn’t keep track of professional clowns specifically (they’re lumped in with comedians, magicians, and other miscellaneous performers), in the mid-2000s, articles began popping up in newspapers across the country lamenting the decline of attendees at clown conventions or at clowning workshop courses. Stott believes that the clown has been “evacuated as a figure of fun” (notably, Stott is personally uncomfortable with clowns and says he finds them “strange”); psychologists suggest that negative clown images are replacing positive clown images.

“You don’t really see clowns in those kinds of safe, fun contexts anymore. You see them in movies and they’re scary,” says Dr. Martin Antony, a professor of psychology at Ryerson University in Toronto and author of the Anti-Anxiety Work Book. “Kids are not exposed in that kind of safe fun context as much as they used to be and the images in the media, the negative images, are still there.”

That’s creating a vicious circle of clown fear: More scary images means diminished opportunities to create good associations with clowns, which creates more fear. More fear gives more credence to scary clown images, and more scary clown images end up in circulation. Of course, it’s difficult to say whether there has been a real rise in the number of people who have clown phobias since Gacy andIt. A phobia is a fear or anxiety that inhibits a person’s life and clown fears rarely rate as phobias, psychologists say, because one simply isn’t confronted by clowns all that often. But clown fear is, Antony says, exacerbated by clowns’ representation in the media. “We also develop fears from what we read and see in the media… There’s certainly lots of examples of nasty clowns in movies that potentially puts feet on that kind of fear,” he says.

From a psychologist’s perspective, a fear of clowns often starts in childhood; there’s even an entry in the psychologists’ bible, the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders or DSM, for a fear of clowns, although it’s under the umbrella category of a pediatric phobia of costumed characters (sports mascots, Mickey Mouse). “It starts normally in children about the age of two, when they get anxiety about being around strangers, too. At that age, children’s minds are still developing, there’s a little bit of a blend and they’re not always able to separate fantasy from reality,” explains Dr. Brenda Wiederhold, a veteran psychologist who runs a phobia and anxiety treatment center in San Diego that uses virtual reality to treat clients.

Most people, she says, grow out of the fear, but not everyone—perhaps as much as 2 percent of the adult population will have a fear of clowns. Adult clown phobics are unsettled by the clown’s face-paint and the inability to read genuine emotion on a clown’s face, as well as the perception that clowns are able to engage in manic behavior, often without consequences.

But really, what a clown fear comes down to, what it’s always come down to, is the person under the make-up. Ringling’s Kiser agreed.

“I think we have all experienced wonderful clowns, but we’ve also all experienced clowns who in their youth or lack of training, they don’t realize it, but they go on the attack,” Kiser says, explaining that they can become too aggressive in trying to make someone laugh. “One of the things that we stress is that you have to know how to judge and respect people’s space.” Clowning, he says, is about communicating, not concealing; good clown make-up is reflective of the individual’s emotions, not a mask to hide behind—making them actually innocent and not scary.

|

| Paul Jung |

Stott, for one, sees clowning continuing on its dark path. “I think we’ll find that the kind of dark carnival, scary clown will be the dominant mode, that that figure will continue to persist in many different ways,” he says, pointing to characters like Krusty the Clown on The Simpsons, who’s jaded but funny, or Heath Ledger’s version of The Joker in the Batman reboot, who is a terrifying force of unpredictable anarchy. “In many respects, it’s not an inversion of what we’re used to seeing, it’s just teasing out and amplifying those traits we’ve been seeing for a very long time.” Other writers have suggested that the scary clown as a dependable monster under the bed is almost “nostalgically fearful,” already bankrupted by overuse.

But there’s evidence that, despite the claims of the University of Sheffield study, kids actually do like clowns: Some studies have shown that real clowns have a beneficial affect on the health outcomes of sick children. The January 2013 issue of the Journal of Health Psychology published an Italian study that found that, in a randomized controlled trial, the presence of a therapy clown reduced pre-operative anxiety in children booked for minor surgery. Another Italian study, carried out in 2008 and published in the December 2011 issue of the Natural Medicine Journal found that children hospitalized for respiratory illnesses got better faster after playing with therapeutic clowns.

And Kiser, of course, doesn’t see clowning diminishing in the slightest. But good clowns are always in shortage, and it’s good clowns who keep the art alive. “If the clown is truly a warm and sympathetic and funny heart, inside of a person who is working hard to let that clown out… I think those battles [with clown fears] are so winnable,” he says. “It’s not about attacking, it’s about loving. It’s about approaching from a place of loving and joy and that when you really look at it, you see, that’s it really genuine, it’s not fake.”

And Kiser, of course, doesn’t see clowning diminishing in the slightest. But good clowns are always in shortage, and it’s good clowns who keep the art alive. “If the clown is truly a warm and sympathetic and funny heart, inside of a person who is working hard to let that clown out… I think those battles [with clown fears] are so winnable,” he says. “It’s not about attacking, it’s about loving. It’s about approaching from a place of loving and joy and that when you really look at it, you see, that’s it really genuine, it’s not fake.”

Thursday, August 01, 2013

Tuesday, July 30, 2013

Sunday, July 28, 2013

MAUDE FLIPPEN BAYLESS: M. Lane Talburt Interview

My Facebook friend Maudie Lou, whom I miss terribly.

Wednesday, July 03, 2013

Tuesday, July 02, 2013

Friday, June 28, 2013

REMINDER

Just a reminder that the International Clown Hall of Fame poster offer ends at 5:00 PM this evening. No orders will be accepted after that deadline. Thanks!

Wednesday, June 26, 2013

INTERNATIONAL CLOWN HALL OF FAME POSTER OFFER: DAY THREE!

Day Number 3 of this limited time offer! For this week only, ending on Friday, 5:00pm CST, the International Clown Hall of Fame is offering this legendary Jim Howle rendered ICHoF Induction poster print of the 1989 inductees!

Lou Jacobs, Emmett Kelly, Red Skelton, Felix Adler, Otto Griebling & Mark Anthony all together as seen by America's premire clown artist! This print alone normally sells for $50.00 and up, and as a special bonus we are including a rare Roy "Cooky' Brown poster, from the WGN Bozo Show that was created especially for Mr. Brown's ICHoF induction.

Two fantastic clown poster/prints for only $40.00...and that includes domestic shipping too! Payments can be made by clicking the "DONATE" button at the ICHOF website, www.theclownmuseum.com under the PayPal link!

100% of the proceeds benefit the ICHOF, its outreach projects and research opportunities.

Monday, June 24, 2013

INTERNATIONAL CLOWN HALL OF FAME POSTER OFFER: ONE WEEK ONLY!

Are there folks out there who would be interested in this Jim Howle print featuring the first six inductees into the International Clown Hall of Fame?

By special agreement with artist Jim Howle, the International Clown Hall of Fame is offering this beautiful print of ICHoF inductees Otto Griebling, Red Skelton, Emmett Kelly, Felix Adler, Mark Anthony and Lou Jacobs. To sweeten the deal we are also offering a limited edition poster of Roy "Cooky" Brown from WGN's Bozo Show.

Both are yours for just $40.00 US, postage & handling (domestic orders only) included.

This is an extremely limited time offer, running from just 2:00 PM EST on Monday to 5:00 PM EST this Friday. After that, this offer is unlikely to be repeated.

To take advantage of this offer simply visit the International Clown Hall of Fame website before 5:00 PM EST on Friday June 28, 2013, click the "DONATE" button and you'll be taken to the ICHoF PayPal link. Send $40.00 with the message "poster offer"and the posters are on their way!

Friday, June 21, 2013

Thursday, June 13, 2013

IN MEMORIAM: Maude Flippen "Flip" Bayless

It is with an extremely heavy heart that we bid farewell to Flip, as warm, kind and as funny a soul as any I've ever met and someone that it was definitely my very genuine pleasure to know...

|

| Photo courtesy of Ron Severini |

|

| Photo by Rosalie Hoffman, courtesy of Ron Severini |

|

| Photo by Rosalie Hoffman, courtesy of Ron Severini |

Wednesday, June 12, 2013

Tuesday, June 11, 2013

Monday, June 10, 2013

Sunday, June 09, 2013

Saturday, June 08, 2013

Friday, June 07, 2013

Thursday, June 06, 2013

Tuesday, June 04, 2013

Saturday, June 01, 2013

Saturday, May 18, 2013

IN MEMORIAM: Juan Muntaynes "Monti" Martinez (1965-2013)

From Raffael de Ritis...

The Catalan artist MONTI (Juan Muntaynes Martinez) passed away last evening at age 48. Actor, director, a great man of theatre, a true genius; friend, brother, master; a model of being humble and generous; but, above all, one the greatest and funniest Spanish clown of our times. He committed his entire life to the theatrical dignity of the traditional and popular art of circus. Gracias, Monti!

Friday, May 17, 2013

CLARK & MCCULLOUGH: The Belle of Samoa (Fox 1929)

From Wikipedia...

Clark and McCullough were a comedy team consisting of comedians Bobby Clark and Paul McCullough. They starred in a series of short films during the 1920s and 1930s.

Bobby Clark was the fast-talking wisecracker with painted-on eyeglasses; Paul McCullough was his easygoing assistant named Blodgett. The two were childhood friends in Massachusetts, and spent hours practicing tumbling and gymnastics in school. This led to their working as circus performers, then in vaudeville. and finally on Broadway. Their hit show The Ramblers (1926) was adapted as a Wheeler and Woolsey movie comedy, The Cuckoos. Clark and McCullough starred in the George Gershwin musical Strike Up the Band on Broadway in 1930.

In 1928 Clark and McCullough entered the new field of talking pictures, with a series of short subjects and featurettes for Fox Film Corporation. In 1930 they signed with Radio Pictures (later RKO Radio Pictures) for six two-reel comedies annually. The RKO comedies are totally dominated by Clark, barging into every scene and monopolizing much of the conversation, with his good-natured buddy McCullough quietly embellishing his partner's antics with subtler gestures and actions. Each film cast the duo in different occupations, which they would tackle enthusiastically if not efficiently. Their names in the films were dictated by their jobs: as lawyers they were Blackstone and Blodgett, as domestic help they were Cook and Blodgett, as photographers they were Flash and Blodgett. Then as now, their fast-paced zaniness is an acquired taste; some audiences enjoy the nutty humor while others do not. The films were re-released in the late 1940s, with exhibitors still divided in their opinions of the team.

Clark and McCullough filmed most of their movies during the summer months, so they could be free to do stage revues during the rest of the year. They appeared in three Broadway shows while their film contract was in force.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)