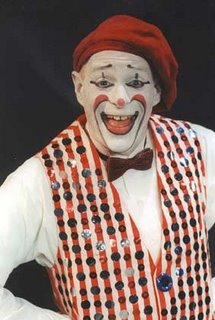

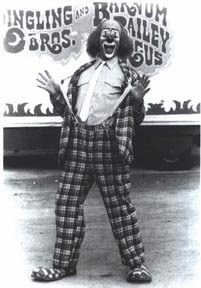

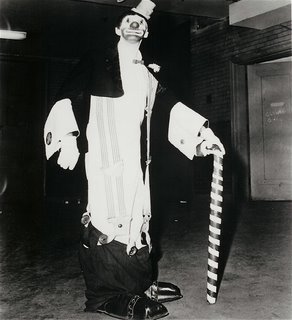

Photo courtesy of Mitch Freddes

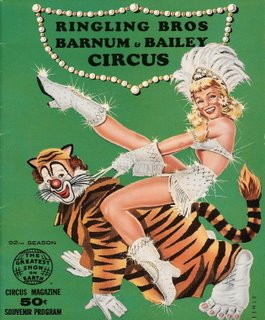

RINGED BY TRADITION

Despite some changes over the years, the unique lifestyle binds circus performers to each other and to their profession.

By Félix Alfonso Peña

Reading Eagle

READING, PA

October 26, 2006

Mitch Freddes was a First of May some 32 years ago when the camel spat on him and that was a good thing, he said.

“If a camel spits on you it's good luck,” said Freddes, who will turn 51 this month and has been a professional circus clown since 1974.

He wasn't too pleased about it at first, “But everybody said to me, ‘That's good. That means you've been initiated.' ”

Initiated or not, he was a First of May the traditional circus term for a neophyte to the veteran circus people until he finished the first year with Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey Circus.

Freddes, who will be performing with the circus today through Sunday at the Sovereign Center, explained that May 1 was the traditional date when circuses started performing and touring every year.

“You really weren't accepted until you made it through one season to another year,” he said. “If you made it from one May 1 to another, you had made it.”

Finding an elephant hair from the tail which was unusual, Freddes said was also seen as an omen of good luck. Performers would often fashion a ring out of it to carry with them.

“And they used to say that if a tiger growled at you, that meant that he liked you,” he said. “That you were accepted.”

In the decades since that first year, Freddes, who later worked for other circuses and has since returned to Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey, has always been a clown.

GREAT DEAL OF CONTINUITY

Looking back on his experiences, he sees some change in the circus world, but a great deal of continuity.

The tent is a thing of the past for Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey, he said.

“We haven't been under a tent since 1956,” he said.

He also said many cities had built arenas that were suitable for circus performances, negating the need for hauling and erecting a canvas tent and offering the advantages of air conditioning.

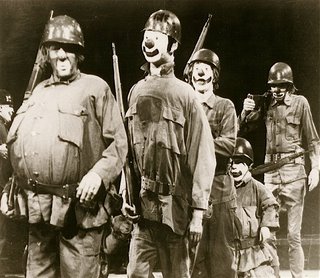

But even as his generation he refers to himself as an old-timer is replaced by new people, circus people are still a closely-knit group, he said, because of their unique lifestyle and their extended time on the road, living and working together, and bound by tradition.

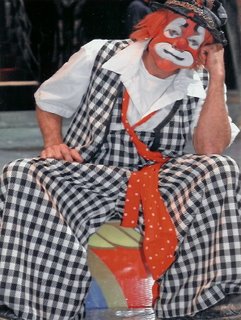

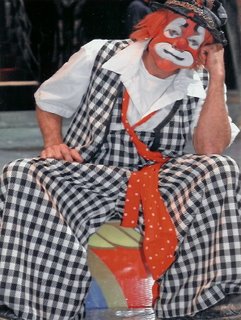

Among the traditions he cherishes are those related to clown alley, an area that dates back to the days of tents.

“Clown alley was behind the tent in the old days,” he said. “Since we used a lot of baby powder, we dressed in an alley so we wouldn't get powder on other costumes.”

“It was a very sacred place,” he said, where other people were seldom or never allowed. “No pictures were ever allowed in there; it was all kept very secret.”

IMPORTANCE OF RINGS

Other traditions highlight the importance of the rings to performers'

lives, he said.

“When you're sitting on the edge of the ring curb,” Freddes said, “you never turn your back to the ring.”

He explained that, rather than superstition, this is simply a show of respect for the area where they must all perform.

“Did you know that the diameter of the ring is 42 feet?” he asked. “It dates back to Roman times? That's the perfect distance that a horse can run around without putting too much strain on its legs.”

Whistling in the dressing room is seen as bad luck, he said, but it reflects a precaution taken in the days when riggers, who set up the rigging for aerial acts and more, communicated with each other by whistling.

“Whistling could be confusing,” he said.

Common sense dictated other rules, such as never facing backward during a parade.

“You need to look where you're going,” he said with a chuckle.

Accidents do happen in threes, he said: “But we don't harp on that too much. All of those things have just come down through the generations.”

Freddes does have what he refers to as a personal superstition, although even that is grounded in experience and precaution.

“Before I go into the arena,” he said, “I untie and retie my shoes. Twenty years ago I was in an act jumping over elephants. One time, I jumped over and broke my ankle. Now I always untie my shoes and tie them nice and tight.”

The circus tradition has become a family one for Freddes, whose parents were not circus performers, but musicians.

“When I was getting out of high school,” he said, “Ringling had a clown college. My mother read an article in the local paper, and she said this looks like something that would be good for you.”

Out of thousands of applications, he said, the college accepted 50, and of those, 10 made it into the show.

PROCESS OF ELIMINATION

“I made it through that process of elimination,” Freddes said. “Then my brothers got involved; they wound up coming into the show in 1975, and continued, working their way up through corporate channels.

“One of my brothers was a vice-president and retired last year. Another is still working.”

His son, 26, was raised on the road, Freddes said.

He said circuses always travel with a teacher for the children, who uses the traveling to good advantage through field trips.

“My wife works for the circus,” he said, “and my daughter travels with

us. She's 3. She's just starting to do some stuff in the ring.

“She's a natural.”

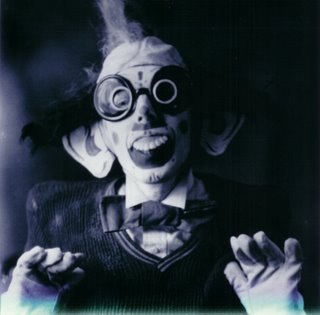

Citing the example of his mentor, Lou Jacobs, who was still performing at age 80 after 60 years as a clown, Freddes looks forward to many more years in the ring and the limelight.

“After all these years, clowning, I call it a career,” he said.

“There's nothing else I would rather do. Some of the things you can't beat are the freedom, the traveling. As many times as I've been around this country and around this world, and things change, it's still beautiful.”